Serious developers serialize their data. Serialization, and conversely deserialization, is the process by which we convert a struct into another form. Typically, we do this for APIs and saving data to a file.

A simple example of this is a CSV file. If we have a list of names and ages, we can “serialize” it as such:

Name, Age

Jess, 18

Norm, 67

Alex, 3This is not the only way. We can also serialize it as a JSON blob:

{

"Jess": 18,

"Norm": 67,

"Alex": 3

}Although there are many practical considerations, my interest is in which serialization method is fastest and most space-efficient.

The Problem

Typically, whenever we need to represent complex data, developers will create structs to define their objects.

// Example Rust struct

pub(crate) struct Product {

pub id: u64,

pub name: String,

pub price: f64,

pub in_stock: bool,

pub tags: Vec<String>,

}When we work with these structs in memory, it’s fairly straightforward. However, when we want to save and load from a file or send it over an HTTP connection, we often can’t use the byte representation directly.

For example, NULL is a programming concept that indicates something is not set (i.e. a dog has no owner). It is typically represented in memory using all zeros 00. Using NULL in your program is fine, but the HTTP standard will interpret a 00 as a closed connection. This might cause problems when a web server tries sending data to your browser.

The solution is to serialize that NULL into something else which the browser can interpret, or deserialize, as NULL. In JSON, we can serialize it using the string literal null:

{

"name": null

}The downside is that serialization and deserialization takes time. Additionally, the space overhead can be quite high. While NULL requires 4 bytes in a program written in C or Rust, the above JSON representation requires at least 13.

Setup

I wrote a simple Rust program to compare the performance of multiple standards. I generate products using a simple function:

pub fn generate_random_product() -> Product {

// Setup code removed for brevity

Product {

id: rng.gen(),

price: rng.gen_range(1.0..1000.0),

in_stock: rng.gen_bool(0.5),

tags: vec!["benchmark".into(), "test".into()],

name: random_string(&mut rng, rng.gen_range(5..10)),

}

}After generating millions of these structs, I then run them against benchmark functions:

fn json_benchmark(data: &Vec<Product>) -> (f64, usize) {

let start = Instant::now();

let mut total_size = 0;

for item in data {

let encoded : Vec<u8> = serde_json::to_string(item).unwrap();

total_size += encoded.len();

let decoded: Product = serde_json::from_str(&encoded).unwrap();

// Prevent dead code optimization

assert_eq!(decoded.id, item.id);

}

let duration = start.elapsed().as_secs_f64();

(duration, total_size)

}This function serializes and then deserializes each generated product. Recording the length of the resulting byte array, and then the total elapsed time, we can understand the performance of JSON:

| Format | Time (ms) | Avg Size (bytes) |

|---|---|---|

| JSON | 48.64 | 117.06 |

| Protobuf | 34.89 | 49.49 |

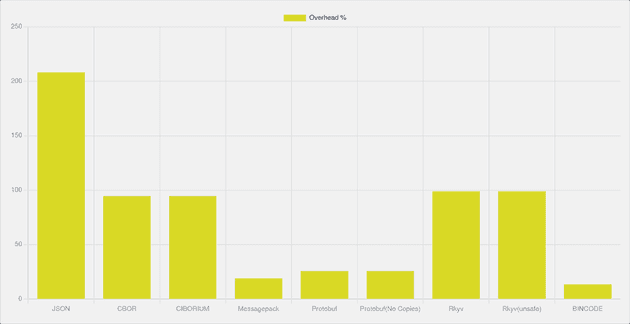

When comparing times, it’s easy to see that Protobuf is much better than JSON. However, this is not very useful for understanding spatial performance. As such, I also calculate the average byte representation of the struct. Theoretically, this will be the minimum size requirement for our structs. We can also use this to calculate the overhead:

This gives us a more useful comparison:

| Format | Time (ms) | Avg Size (bytes) | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|

| JSON | 48.64 | 117.06 | 216.38% |

| Protobuf | 34.89 | 49.49 | 33.76% |

| Theoretical | N/A | 37.00 | 0.00% |

Issue with BSON

thread 'main' panicked at src/main.rs:144:40:

Failed to serialize to BSON: UnsignedIntegerExceededRange(11239684465121854171)

note: run with `RUST_BACKTRACE=1` environment variable to display a backtraceI wanted to benchmark BSON, a binary representation of typical JSON. Though the bson library supports signed 64 bit numbers, it appears that it does not support 64 bit unsigned numbers. I decided not to test this standard.

First Experiment

I ran all these experiments on my Framework Laptop. All time data should be used relative to each other. Performance will vary across devices.

Spatial data should be consistent across all devices.

To start I ran benchmarks on 6 different serializers:

| Format | Time (ms) | Avg Time (ns) | Avg Size (bytes) | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSON | 344.71 | 344.71 | 114.06 | 208.28% |

| CBOR | 373.18 | 373.18 | 72.00 | 94.60% |

| Messagepack | 276.87 | 276.87 | 44.00 | 18.92% |

| Protobuf | 249.61 | 249.61 | 46.50 | 25.67% |

| Rkyv | 142.98 | 142.98 | 73.60 | 98.93% |

| BINCODE | 141.66 | 141.66 | 42.00 | 13.51% |

| Theoretical | N/A | N/A | 37.00 | 0.00% |

Before breaking these down, I noticed some strange issues I hadn’t expected. For example, I figured CBOR would likely be more performant. Looking through the data, I noticed the library I was using serde_cbor had actually been deprecated. I decided to also try the CIBORIUM library as it seems better supported.

Next, I noticed that my implementation for Protobuf seems worse than I expected. I decided that the issue related to how I was forced to copy the data into the Protobuf representation struct (unlike JSON or Messagepack that could use Product directly):

for item in data {

let proto = ProductProto {

id: item.id,

name: item.name.clone(),

price: item.price,

in_stock: item.in_stock,

tags: item.tags.clone(),

};I moved this cloning action outside of the benchmark to improve performance. In practice, developers are likely to utilize these Protobuf defined structs more directly.

Finally, I noticed that rkyv, a zero-copy serializer, under-performed compared to other libraries. It was way slower than I would have expected.

fn rkyv_benchmark(data: &Vec<Product>) -> (f64, usize) {

let start = std::time::Instant::now();

let mut total_size = 0;

for item in data {

let encoded = to_bytes::<Error>(item).expect("Failed to serialize with rkyv");

total_size += encoded.len();

let decoded = rkyv::access::<product::ArchivedProduct, Error>(&encoded).expect("Failed to access archived data");

// Prevent dead code optimization

assert_eq!(decoded.id, item.id);

}

let duration = start.elapsed().as_secs_f64();

(duration, total_size)

}I tried using the unsafe version of the deserialize as well, but it only improved slightly. I may followup later to update the benchmarks if I have time to come back to it.

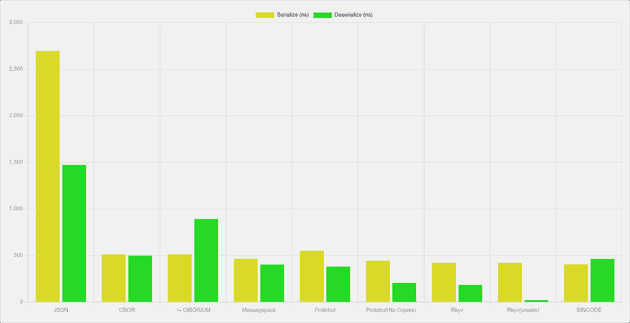

Finally, I realized that we are combining serialize and deserialize times. This is not necessarily useful. Instead, I will run the experiment twice. Once, I run both, and the other will only run serialization. By subtracting these numbers, I can derive the deserialization time.

Second Experiment

All together, I generated the numbers below:

| Format | Serialize (ns) | Deserialize (ns) | Avg Total (ns) | Avg Size (bytes) | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSON | 112.14 | 242.86 | 355 | 114.06 | 208.26% |

| CBOR | 144.95 | 233.88 | 378.83 | 72 | 94.59% |

| ⮡ CIBORIUM | 156.18 | 459.98 | 616.16 | 72 | 94.59% |

| Messagepack | 95.62 | 181.83 | 277.45 | 44 | 18.92% |

| Protobuf | 107.25 | 143.71 | 250.96 | 46.5 | 25.66% |

| ⮡ No Copies | 52.15 | 137.7 | 189.85 | 46.5 | 25.66% |

| Rkyv | 98.25 | 41.7 | 139.95 | 73.6 | 98.92% |

| ⮡ unsafe | 96.95 | 14.8 | 111.75 | 73.6 | 98.92% |

| BINCODE | 34.65 | 113.17 | 147.82 | 42 | 13.51% |

| Theoretical | N/A | N/A | N/A | 37 | 0.00% |

First, JSON is a sub-optimal serialization standard. It’s by far the worst spatially (with a whopping 208% overhead). It also is one of the worse in terms of time. Unsurprisingly, this is likely due to the way JSON includes so many verbose symbols (i.e {, ,, ", [, etc). JSON also includes keys that represent the full variable name on the struct (e.g. in_stock, names, etc). Below, we can see an example of JSON and its inefficiency. Each character (letters, punctuation, etc) equals 1 byte that needs to be stored.

{

"id": 15329797176529828000,

"name": "4BfcB",

"price": 983.5090278630428,

"in_stock": true,

"tags": [

"benchmark",

"test"

]

}CBOR, a standard advertised to be more efficient than JSON, was also surprising. It performed the worst in time, and the second worst in space usage. Additionally, the non-deprecated library CIBORIUM performed significantly worse than any other library I tried. Either my implementation is wrong, or there is significant room for improvement.

Both Protobuf and rkyv significantly improved in performance when compared to the first run. Ignoring the conversion between proto and non-proto versions of the struct cut serialization time in half. Conversely, the unsafe rkyv benchmark reduced deserialization by around 75%!

Finally, BINCODE, though it didn’t have the best total time, had by far the best serialize performance. It also had the best spatial performance. Though Messagepack had nearly identical space performance (with only 2 extra bytes).

Third Experiment

I also want to understand how large structs affect performance. Instead of generating the name field as a string of lengths 5 to 10 (e.g. 4BfcB54), I generated lengths between 5,000 to 10,000 (i.e. 7Aaa13...81PgC). These larger values skew the results in a few interesting ways:

| Format | Serialize (ns) | Deserialize (ns) | Avg Total (ns) | Avg Size (bytes) | Overhead |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JSON | 2693.91 | 1473.1 | 4167.01 | 7607.86 | 1.02% |

| CBOR | 510.44 | 498.87 | 1009.31 | 7567.8 | 0.49% |

| ⮡ CIBORIUM | 511 | 891.06 | 1402.06 | 7567.8 | 0.49% |

| Messagepack | 463.65 | 402.84 | 866.49 | 7539.8 | 0.12% |

| Protobuf | 551.24 | 380.01 | 931.25 | 7541.29 | 0.14% |

| ⮡ No Copies | 445.01 | 206.05 | 757.29 | 7541.29 | 0.14% |

| Rkyv | 420.81 | 184.45 | 605.26 | 7569.3 | 0.51% |

| ⮡ unsafe | 421.1 | 21.39 | 442.49 | 7569.3 | 0.51% |

| BINCODE | 403.93 | 464.15 | 868.08 | 7537.8 | 0.09% |

| Theoretical | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7530.8 | 0.00% |

First, the overhead for space usage drops significantly. Because it always requires 8 bits to represent each of the character, each serialization standard is forced to use the same 8 bits. Only JSON used more than 1% of total space for serialization. Otherwise, overhead is negligible.

In terms of time, JSON and CBOR are the clear losers. Protobuf, Messagepack, and BINCODE all have fairly similar performance, with Protobuf (No Copies), having better deserialize performance.

The main stand out is that rkyv with unsafe deserialization had by far the best deserialize performance. While most took more than 300.00 ns to deserialize, rkyv pushed past the competition with only 21.39!

Analysis

I went in with a few preconceptions that have since been heavily clarified. First, as expected, JSON performed very poorly. Ironically, it is perhaps the most well used of all the serialization standards.

I also believed that Protobuf was a standout performer. Unfortunately, it appears rather middling. It’s slightly better on the deserialize, but it wasn’t much better than Messagepack or BINCODE. Previously, at an old employer, I had done some preliminary investigations to serialize payloads for use in emails to customers. I had identified Protobuf as much better than other options. For this example struct, at least, Protobuf was not the best .

Next, I expected that rkyv would be the best standard, but I was surprised by its serialization performance. It appears as though rkyv is much better suited to read-heavy applications (i.e. reading from a file) than serialization. It was also fairly heavy in the space requirement as well. It’s clear that rkyv is not always the best choice depending on your use case.

Finally, large payload strings greatly affected performance. Space overhead shrunk fairly quickly, becoming almost inconsequential. serialization performance suffered fairly equally for all standards, and deserialization performance likewise with the exception of rkyv.

Conclusion

Some standards performed better than others. For example, based on my findings, you should probably not use JSON. If raw performance is your concern, all APIs should return Protobuf or BINCODE. Though rkyv isn’t traditionally designed for APIs, its deserialization speed suggests it could be valuable in read-heavy scenarios.

Of course, raw performance is not the main factor in how we pick a format. JSON, though it’s very inefficient, has huge benefits that often outweigh performance. For example, it’s fairly human readable and widely supported. The ubiquitousness of JSON outweighs any potential competitor. Pure momentum and tradition prevent any true challenger from replacing this standard.

Finally, you should consider whether your application is read or write-heavy. The former will require a standard with high serialization performance, while the latter benefits from fast deserialization. This can be the difference between choosing rkyv or BINCODE in your next project.